There was a time not too long ago when nobody in America knew anything about Italian food.

Well, a few people did—because they had moved here from Italy. Everyone else was clueless, or close to it. Americans loved pizza and lasagna and heaping platters of spaghetti and meatballs, sure. They loved a certain style of cooking that had originated with immigrants from southern Italy, primarily Sicily and Naples, and which had (like Cantonese food) endured a curious process of Americanization. But how actual Italians ate—that was another matter.

Fifty years ago, French gastronomy reigned as the aspirational cuisine of choice—for restaurant diners and for home cooks. But we were in the dark ages when it came to regional Italian cooking. We didn’t know about fresh pasta, or why the shape of the pasta is as important as the ingredients in the sauce. We’d never heard of pesto or risotto or pancetta. Hell, we didn’t even know from Parmigiano Reggiano.

All of these remained a faraway mystery to the average eater. And then one woman changed it all and turned us all into amateur Italians. You may know her because of certain dishes of hers that have come to be deified. Lemon roast chicken. Tomato, butter, and onion sauce. Her Bolognese. Probably you know her simply by her first name:

Marcella.

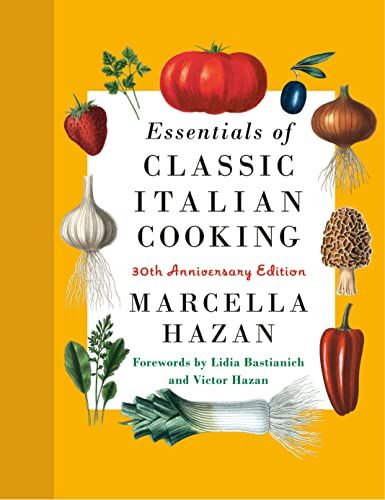

That would be Marcella Hazan, part of a holy trinity of teachers, including Julia Child and Madhur Jaffrey, each of whom demystified one of the world’s major cuisines for Americans trapped in a Wonder Bread world. Hazan’s first two volumes, The Classic Italian Cookbook (1973) and More Classic Italian Cooking (1978)—later combined as The Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking (1990)—secured her legend.

Because she wasn’t a TV personality, Hazan’s impact is felt chiefly through her recipes, making her more mythic yet more approachable at the same time. Over a decade after her death, her legacy is only growing, with reissues of her cookbooks—the latest, published this past fall, of Hazan’s third book, Marcella’s Italian Kitchen—and a feature documentary currently making the rounds on the festival circuit and due for a theatrical release in May 2025.

Part of her longevity is due to the fact that Italian food is still indisputably popular. Pizza is probably the world’s favorite food—and these days we can make incredible pizza at home. Many of us have access to better produce than we would’ve had in, say, 1957; we have farmers’ markets, CSA boxes, co-ops, Whole Foods and Sprouts and Erewhon. The culture of Italian gastronomy dovetails with contemporary trends: it’s vegetable-forward and unpretentious, and it involves a lot of olive oil. American chefs who specialize in different visions of Italian cuisine—Nancy Silverton, Evan Funke, Marc Vetri, Angie Rito & Scott Tacinelli, Rita Sodi & Jody Williams—have become national stars.

Still, as Funke and Sodi could tell you, there are rules (at least when it comes to true Italian tradition). And they are unbending. Marcella Hazan, in her day, proved a stern—eye-rolling, dismissive, intimidating—taskmaster. She wanted you to do it right, and she understood that rigor is the only pathway to achieving simplicity.

I know because Marcella Hazan changed my life, too—or at least my relationship with cooking. As a latch-key kid in the 1980s, raised by a single parent, I faced a nightly choice: help make dinner or wash the dishes. My mother, a skilled and adventurous home cook, rarely followed recipes unless she was baking. Improvisation ruled: julienned strips of red bell pepper or thinly sliced red cabbage made their way into a salad simply to add “color and crunch.”

Meanwhile my aunt and her husband adopted a more Italian approach to cuisine and lifestyle. Dinner would start with an appetizer and a glass of wine. Then to the table for a modest first course, usually a pasta, followed by a meat dish with a cooked vegetable. Talk, drink, talk, before they finished with an espresso and a square of chocolate for dessert.

The concise portions didn’t leave me hungry, exactly, but I did wonder: If this was all so good, wasn’t there more of it?

By high school, I started to cook with tentative ambition. When I bragged to my aunt that I made my own sauce with canned tomatoes, onion, and lots of garlic and olive oil and who knows how many spices, she blanched. “I would make five different sauces out of those ingredients,” she said.

That’s when she introduced me to Marcella.

“Marcella clarifies how to pare down, as opposed to build up, a dish,” my aunt said. She explained that a sauce with tomato and butter is going to taste a lot different than one with garlic, parsley, and olive oil. And of course that was true. Marcella knew.

“All that really matters in food is its flavor,” Hazan wrote in Marcella’s Italian Kitchen. “It matters not that it be novel, that it look picture-pretty … Do not strain for originality. It ought never to be a goal, but it can be a consequence of your intuitions. If the purpose of flavor is to arouse a special kind of emotion, that flavor must emerge from genuine feelings about the materials you are handling. What you are, you cook.”

Do not strain for originality. That Strunk-and-White directness seems like a total buzzkill, at first. And yet the first Hazan recipe I tried—balsamic strawberries—taught me to shaddap and do as I was told.

About those strawberries: From Marcella’s Italian Kitchen, this is a radically simple, happy-accident sort of dish that Marcella concocted in an effort to spruce up out-of-season fruit. Wash two pounds of strawberries in cold water. Hull them and then slice them in half. Let them sit in four to six tablespoons of sugar for twenty minutes. Before serving them, splash them with a couple of tablespoons of balsamic vinegar. Boom. The tart syrup makes the berries taste more like themselves, but also something elevated.

This was not the Italian food I knew.

Of course, the notion of “Italian food” could only be ludicrous to Hazan—or to anyone from Italy, which (like China and Mexico and India) is best viewed as a conglomeration of regions. Hazan was a scientist by training; she held doctorates in natural science and biology. To her Italian cuisine meant regional cooking, each region with its own climate, ingredients, recipes, dialects, strong opinions, and ancient traditions.

“We thought we knew Italian cuisine, but we didn’t,” says author Ruth Reichl, the former editor of Gourmet magazine and onetime restaurant critic for both the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, who’d been covering food for a decade before she first tasted balsamic vinegar in the late ’70s. “It was shocking. It was delicate. Not a lot of garlic it in—it’s about finesse, not bold, hearty flavors. When I was a critic in San Francisco,” says Reichl about the late ’70s and early ’80s, “restaurants often said they were using Marcella’s recipes. She was that important.”

Hazan didn’t start cooking until she and her husband, Victor, moved to New York in the mid-1950s. Hazan thrived as a home cook, and by the early ’70s she was teaching a class on Italian food and culture—a class that came to the attention of Craig Claiborne, the powerful food editor of the New York Times. The queenmaker wrote about Hazan, and within a year she had a book deal.

Hazan had no interest in writing in English. Victor served as her translator and champion and first-go editor, insisting on turning her improvisations into exact measurements. “She was a fun, cantankerous, and intelligent person,” says David Kamp, who interviewed Hazan for his 2006 book The United States of Arugula. “She hated the minstrel of the Italian mama that says, ‘Mangia, Mangia!’ She’s didn’t fit any stereotypes of Italian cooking. She was an intellectual who wasn’t trying to be telegenic or fun, she was just saying this was the right way to do it.”

Her pot roast is humble enough for Sunday dinner but impressive enough that I served it for Christmas one year. The roast braises in a half a bottle of red wine, which hardly seemed like enough the first time I tried it, yet it wasn’t overwhelmingly meaty or fatty the way a traditional pot roast can be; neither floral or vegetal but clean tasting in a similar way. Warming without being greasy. Hazan was adamant about her methods because they worked.

“Unlike with most cookbooks,” says Reichl, “her recipes are utterly reliable—other than the portions might be smaller than Americans want. You’ll never make a mistake with a Marcella recipe.”

This is why American home cooks continue to return to Marcella, in spite of the thousands of Italy-centric cookbooks at their disposal. (How many are published each year? Maybe 800?) Like all great teachers, Hazan gave us skills beneath the recipes. She wanted us to develop the culinary equivalent of a musical ear. Do you stir now? Is it too dry? Is it too wet?

“Recipes endeavor to teach us, but you’ve got to pay attention and that takes time,” says food writer Peter Barrett, who covers the realm of home cooking in a Substack newsletter called Things on Bread. “What makes Italian cuisine so appealing is that if you have great ingredients, you can make it perfectly.” The beauty in a meal, as in a painting, arises from the nuance of details. That’s especially true with Italian cuisine. If a recipe employs little more than olive oil, tomatoes, basil, mozzarella, and salt, you realize quickly that everything will start to taste way better as soon as you pay attention to where the olive oil, tomatoes, basil, mozzarella, and salt come from. Your thinking shifts. A well-made Italian meal offers not only a mode of sustenance, but a way of living.

“The succession of the courses has a true meaning in terms of health, in terms of pacing yourself, everything at that certain moment,” says Beatrice Ughi, owner of Gustiamo, the indispensable purveyor of fine Italian products. “This is how we eat. Simplicity, which is the most difficult thing to accomplish. Like Morandi’s work, the bottles, the space, the shadows, it’s very simple. There are certain rules, and they are not arbitrary.”

The limitations are the inspiration.

A grouping of slender glass water bottles rests on a shelf in my aunt and uncle’s apartment. The still life is their tribute to Giorgio Morandi’s still life paintings, which have a looseness and tightness that never reconcile; their nuance and beauty rest not in cleverness but in their restraint, attention to detail, and in the human hand that made it. “Marcella, like Morandi,” says Barrett, reminds us “just how profound and eternal the everyday can be when handled reverently.”

I would not say I am a religious person except that I have sought spiritual answers in traditional everyday pleasures. Cooking, conversation, connection, and Marcella’s strawberries—my faith is anchored there.

Read the full article here